Why there are less women in STEM

Out of 970 Nobel Prize Winners, only 65 are women. Only 26 women, not just above one-third of them, won a Nobel in natural sciences, with Marie Curie being two times in this list. In comparison, 620 men, nearly two-thirds of the men laureates, won the award in natural sciences. These numbers show us the great underrepresentation of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). While the lack of women in the Nobel laureates is the peak of the gender gap in STEM, it is really just the result of a complex problem rooted in our history and social norms.

Gender differences in STEM don’t only show in these very selective, high achievements such as the Nobel Prize, but also in university programs. Overall Europe, men are more likely to choose an enrollment and to graduate in STEM fields. In 2020, Macedonia and Liechtenstein were the only countries, where female graduates outnumbered males. Only in the technological sciences, there were 57% male graduates. Still, the Macedonian gender gap in STEM graduates was the lowest in Europe with 6.6 women and 6.2 men per 1000 habitants (age 20-19) graduating in STEM. It is notable that, overall, fewer people are graduating in STEM fields (6.4 graduates per 1000 young habitants) than the European average (18 graduates per 1000 young habitants).

With a gender gap in STEM of -0.4, Macedonia seems quite progressive in this regard. Still, it is placed 73rd in the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) Report issued by the World Economic Forum. Iceland takes the top spot while having a gender gap of 5.5 in STEM graduates (17.2 male and 11.7 female graduates per 1000 young habitants). It seems like the more equal women are and the more choice they have, the more they choose to study humanities. This unintuitive correlation is also referred to as the “Gender Equality Paradox” (Stoet and Geary, 2018). In this study, it was suggested that women in richer, more gender-equal countries are less pressured by economic factors, so they pursue careers out of relative strengths and interests, which seems to be more in the humanities.

This study was widely discussed, even outside the academic papers. It seemed to question all efforts towards bringing women into STEM fields. It also seemed to confirm the old stereotype that men lean more toward technical interests, while women are more interested in working with people. If that is true, what is the point of trying to include women in STEM anymore?

Two years later, Sarah Richardson and her colleagues published a response, questioning not only the calculations of the data used in the original study but also the assumptions that lie underneath and the conclusions drawn from the results if the data are correct.

The first and most important assumption is that a higher GGGI means that there is more gender neutrality in the country. What seems logical at first, gets more complex as the data used to calculate the GGGI measures women’s participation in different broad domains, not the participation differences in explicit fields of work. Also, it doesn’t measure psychological factors like stereotypes in society. Even if a domain seems equally divided between men and women at first, there could be a great equality variety in that field. For example, the managing occupations in the US are nearly equally divided, with women holding 52% of them. While this remains true for some positions like sales managers (48% women), this number doesn’t show the differences in other fields. Only 12% of architectural and engineering managers are women, while they make up 78% of human resource managers. It becomes clear that even in countries with high gender equality, there is no gender neutrality and there are still differences in occupation which reproduce stereotypes.

Another assumption regarding the data about female and male graduates is that university programs are categorized in the same way in all countries. In fact, the programs are not standardized. That means which degree programs are categorized as STEM can vary from country to country. For example, whether health professions such as health services are included or excluded in STEM programs changes women’s overall participation in STEM, since they are overrepresented in this field.

These considerations show how complex the subject really is. The answer to this paradox is probably more complex as well. There are different approaches to explaining the data, also suggested by Richardson and her colleagues, including historical, cultural, and social factors.

The most obvious and common explanation is that women choose different career paths because of stereotypes. In postindustrial countries, STEM is highly associated with men. From a young age, STEM subjects are promoted to them more than to women. Women may prefer the humanities not because of their biology, but because of their socialization. This association is rooted in the history of each culture and could be more present in richer and high GGGI countries, like Norway (ranked 2nd place globally) as in low GGGI countries like Iran (ranked globally in place 143).

Other aspects to consider are the available degree programs and travel to pursue STEM degrees in other countries. If there are mainly STEM degree programs available, more women will also choose to study in this degree. Also, the plain data don’t show the people that study in a foreign country. If more men go abroad to get degrees and more women stay in their country, a lot of men don’t show up in the data, even though they study STEM, while most of the women are counted.

Lastly, higher education is still correlated to privileged classes. Especially, but not only, in countries, where education isn’t as easy to access, students are more likely to come from academic and wealthier families. Women in higher classes pursue higher education more often than less privileged women and men. These women are more likely empowered to resist gender norms, while less privileged women live with stronger stereotypes around them.

The Gender Equality Paradox could have many explanations, most likely it’s a mixture of them all. It is too easy to just put it on biological or interest differences between men and women. Society is far more complicated than that, which is why it is a difficult and long process to make a change. Anyway, the Gender Equality Paradox isn’t so paradoxical, it is just a complex problem with complex answers. This is why there is still a need for further research. In the meantime, it is important to keep promoting STEM to women and creating safe workplaces. Besides having stereotypes, the male-dominated fields tend to be less flexible, making it hard for women with families to work there. As a result, a lot of women who finally decide to study STEM are not working in the industries, but in teaching and education.

Having the possibility to go into STEM isn’t enough to have equal gender representation. To have actual gender equality, many aspects can be improved to this day, in every country.

Johanna Krautkrämer

Sources:

Nobelists.org – Nobel laureates

Undp.org – The Journey of Women in STEM – Insights and Recommendations from North Macedonia

Weforum – Global Gender Gap Report 2023

Ec.europa.eu – Graduates in tertiary education, in science, math., computing, engineering, manufacturing, construction, by sex – per 1000 of population aged 20-29

Genderscilab.org – If not a paradox, then what? 7 alternative explanations for the inverse correlation between the Global Gender Gap Index and women’s tertiary degrees in STEM

Genderscilab.org – Gender Equality ≠ Gender Neutrality: When a Paradox is Not So Paradoxical, After All

En.wikipedia.org – Gender-equality paradox

Globaldiversitypractice.com – Where are the women in STEM?

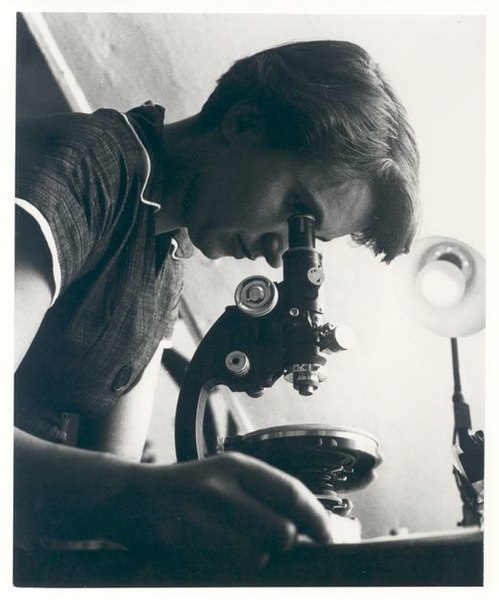

Photo: Wikimedia commons – MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

Leave a comment