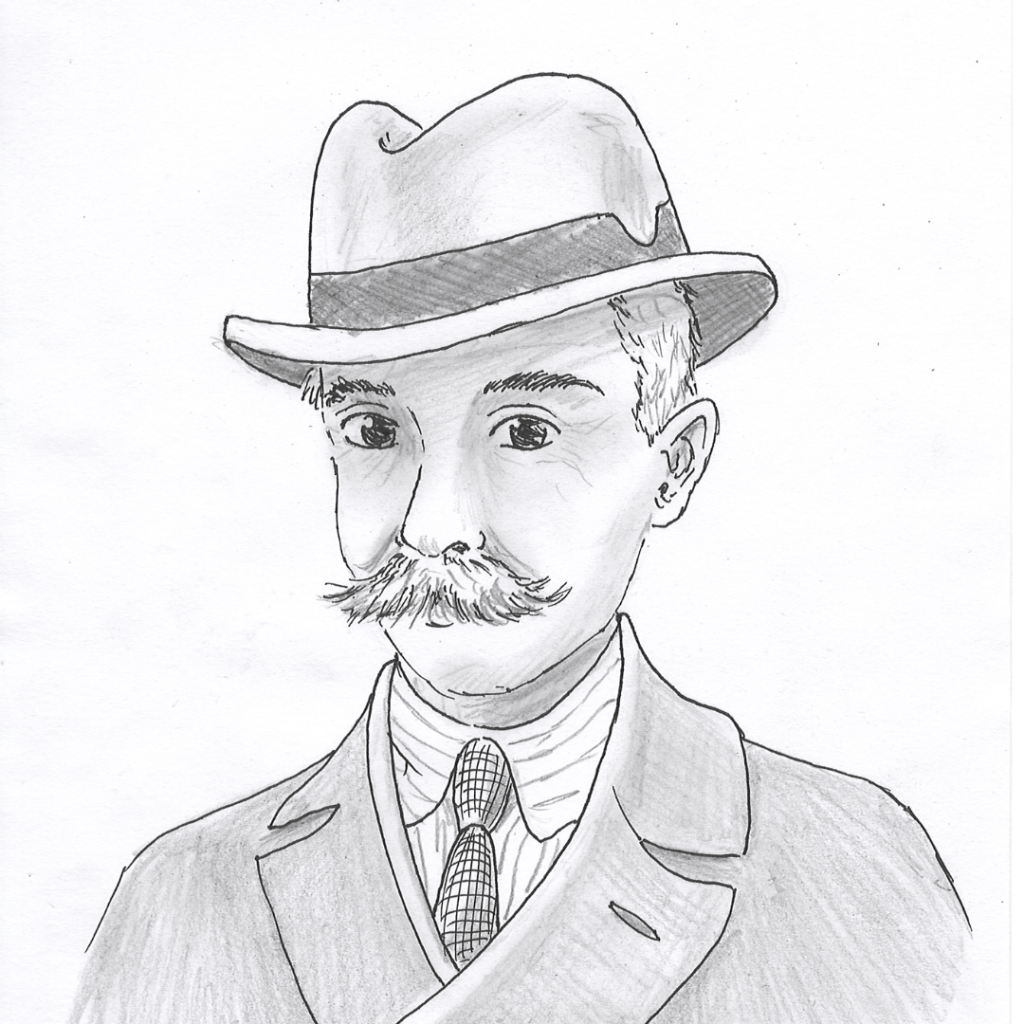

“De Coubertin” is not the most famous French name you might know, I presume. I must admit it is not very well-known in France either. Although without him, hosting the Olympic Games in Paris in 2024 would have sounded like a historical old-fashion joke to most of us.Let me tell you a little more about the so-called father of the modern Olympics!

De Coubertin, sport and pedagogy

The Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who first opened his eyes in Paris in 1863, was born to be a gainsayer; a man that comes to make a change. With a triple diploma in literature, law and sciences, Coubertin was likely to pursue a military or a diplomatic career – as his aristocratic family would have wished for. However, Pierre de Coubertin had always been fascinated by sport. From a very young age, he excelled at pistol shooting, and even became French champion on several occasions. His interest then developed in so-called “Anglo-Saxon” sports, which he discovered and practiced during his many stays in England: rowing, boxing, fencing and horse riding.

At that time, sport was much more firmly established in the British school curricula than in the French one, and De Coubertin drew inspiration from this pedagogy to carry out a major school reform on his return. His main motivation was to improve the physical condition of the pupils for their own well-being, but also to “regenerate the French race which had been weakened by the defeat of the war in 1870” (the Franco-Prussian war). The military spirit that mum and dad wished for him wasn’t so far away, after all…

It was this reform, which he had to persevere with in order to make the rigid French academies more flexible, that was to serve as a training ground for the battle he engaged to re-establish the Olympic Games, year after year. His first project was hardly put together in 1889, then supported by the young IIIrd Republic, and finally officially presented in Paris in 1892. He was only 29 at the time!

The rise from the ashes

His idea was to bring the Olympics up to date again, 15 centuries later, modernized and with a cosmopolitan character. Coubertin believed that to make sport more popular, it had to be globalized. The aim was also to promote understanding between peoples, which had been severely damaged by the wars of the century.

Indeed, the original Olympic Games were abolished in 393 by decree of the Christian emperor Theodosius, who put an end to the practice of pagan cults. The Olympics, organized to honor the gods of Olympus, therefore fell into this category and were abolished. Earthquakes have since completely destroyed the sites where the games were held, and not a single building from the period is still visible.

Of course, de Coubertin was not the first to attempt to re-establish the Olympic Games or to create a similar event: the Olympiades de la Republique in Paris, the Zappa Olympiad in Greece, or the Olympian Games in England, were held for a few editions. But it was Coubertin’s tenacity and enthusiasm that enabled his Games, unlike other similar sporting events, to endure over time.

The International Olympic Committee

In 1894, when all the hand-shakings and endless speeches eventually rewarded him, De Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee to provide practical assistance to his project, to bring everything together under a single umbrella and to decide where the Olympics would be held. Dimitrios Vikelas, a Greek businessman and writer (his nationality was purposely sorted) was to hold the presidency of the Committee, followed by the Baron himself from 1896 to 1925.

It is within this very Committee that the various elements that make up the symbols and values of equality and international fair play of the Olympic Games will be invented.

The motto came first: Citius, Altius, Fortius, a Latin expression meaning “faster (athletically), higher (intellectually), stronger (spiritually)”. This expression was invented by one of De Coubertin’s collaborators. Then came the credo: “The most important thing at the Olympic Games is not to win but to take part, because the important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle; the most important thing is not to have won but to have fought well“, written by De Coubertin and inspired by the words of a priest he admired. The world-famous Olympic rings were designed by De Coubertin himself and have remained virtually unchanged since 1913. They represent the 5 continents and the universality of the Olympic spirit.The Baron also wrote the Olympic oath: “On behalf of all competitors, I promise that we will take part in these Olympic Games respecting and following the rules that govern them, in a spirit of sportsmanship, for the glory of sport and the honour of our teams“, which is now pronounced by an athlete, a judge and a coach from the host country.The Olympic flame was obviously not invented by De Coubertin. It was already existing during the original Olympics in Greece, permanently burning on the altar of Zeus. The modern flame was lit for the first time in 1932, and little by little the idea emerged that it could be lit directly by the rays of the sun in Olympia and then transported, still burning, to where the games were being held.Last but not least, the Olympic anthem Cantata by poet Kostís Palamás, set to music by composer Spýros Samáras in 1896, was also played at the first Olympics in Athens, then in Paris in 1900, Saint-Louis in 1904, London in 1908, Stockholm in 1912, etc. It was not until 1994 that the Games were staged alternately every 2 years.

This story, that created the Olympic Games as we know them nowaday, has not been a fairy tale from the beginning, and all editions were not models for the collaborative and inclusive spirit that was to underpin their resurrection. Some editions tried to set up “anthropological days”, reserved for “representatives of wild and uncivilized tribes”, while others wanted to involve only jury members of the same nationality. De Coubertin himself, although being part of a better global collaboration, spoke against female’s sport, being “impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic”, and no women were allowed on the olympic sport fields for the very first edition. The paralympic athletes, at last, had to wait until 1948 to be able to participate, after De Coubertin’s death in 1937.

So is humankind, like the Olympics: after ban comes inclusion!

Zoé

Leave a comment