Hangul, the Korean alphabet, is often cited as one of the most logical and accessible writing systems in the world. Yet few people know that it was not the result of a slow evolution over centuries, but rather the outcome of an enlightened political decision driven by a concern for social justice. Let’s look back at the history of an invention that was as revolutionary as it was humanistic.

Until the 15th century, Korea did not have its own alphabet. The spoken language of the people was Korean, but official and scholarly texts were written using Chinese characters (hanja). Only the intellectual and aristocratic elite, known as the yangban, mastered these complex characters. As a result, the majority of the population was excluded from reading, writing, and, more broadly, access to knowledge.

In this rigid society, education was a privilege reserved for the few. While the people had a rich oral tradition, they had no way to express their thoughts in writing using their own language. It was in this context that a major historical figure emerged: King Sejong the Great.

Ascending the throne in 1418, King Sejong is now considered one of the greatest rulers in Korean history. A man of letters with a deep passion for science and the arts, he also cared deeply about the well-being of his people. Recognizing that illiteracy was holding back social and cultural development, he decided in 1443 to create a new Korean alphabet simple, logical, and accessible to all. (Korean Cultural Center, Paris)

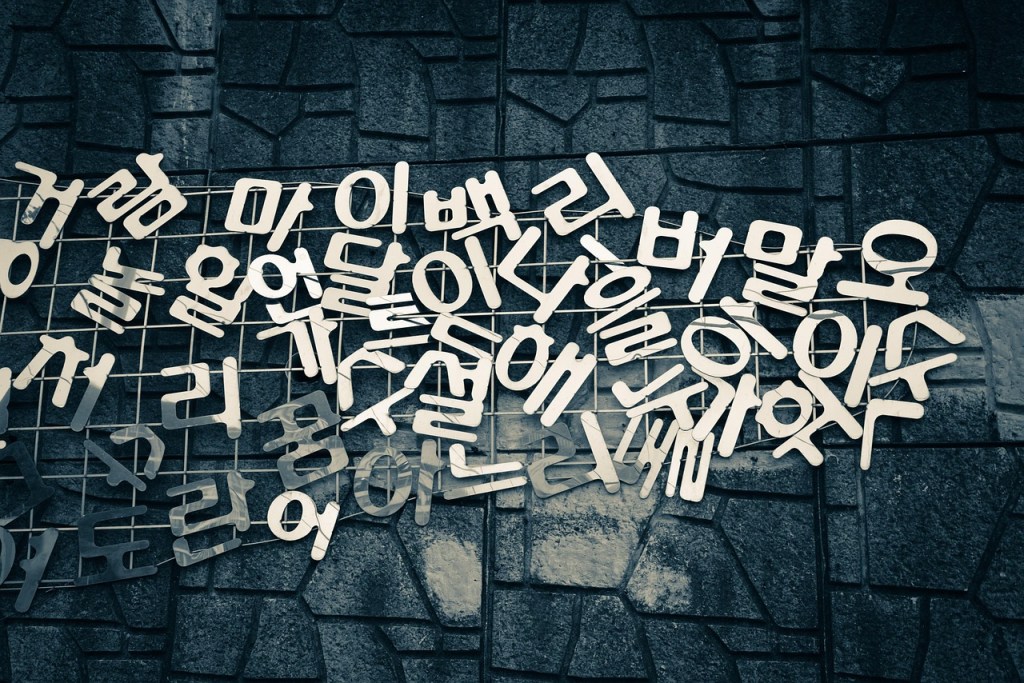

This project was not only political but also a linguistic masterpiece. Hangul, originally named “Hunminjeongeum”, meaning “the correct sounds for the instruction of the people,” was designed to accurately reflect the Korean language while being easy to learn and use, even by the lower classes. (Wikipédia)

Unlike Western alphabets or Chinese ideograms, Hangul was scientifically designed. Its original principle was unique: the shapes of the letters are based on the position of the vocal organs used to pronounce them. For example, the consonant ㄱ represents the shape of the tongue when pronouncing the [k] sound. (Korean Cultural Center, Paris)

Initially, the system included 28 letters: 17 consonants and 11 vowels. Today, 24 are still in use (14 consonants and 10 vowels). These letters are combined into square-shaped syllabic blocks, each representing a full syllable. This visual format makes reading intuitive once the sounds are learned.

When it was first introduced, Hangul was harshly criticized by the aristocracy. The yangban saw it as a threat to their intellectual authority, since making writing accessible meant challenging the established social order. For centuries, Hangul was mostly used by women, children, and the common people, while official documents continued to be written in classical Chinese.

It wasn’t until the 20th century through Korea’s independence and movements toward modernization and democratization that Hangul was fully adopted as the official alphabet of South Korea (and in a modified form in North Korea).

Today, Hangul is much more than an alphabet, it is a symbol of Korean identity and sovereignty. Every October 9 in South Korea (and January 15 in North Korea), a national holiday known as “Hangul Day” celebrates this unique invention. Many linguists consider Hangul to be one of the most rational writing systems ever created.

In a world where illiteracy remains a global issue, the story of Hangul reminds us that a well-designed linguistic tool, supported by political will, can deeply transform a society. By making reading and writing accessible to all, King Sejong not only achieved a technical innovation but also made a profoundly democratic gesture.

Narjesse Ahrrouq

Sources:

https://www.coree-culture.org/

https://parlonscoreen.fr/hangeul-alphabet-coreen-le-guide-ultime/

https://bonjour-coree.org/lhistoire-du-hangeul-%ED%95%9C%EA%B8%80-alphabet-coreen/

Leave a comment