“We must not ask ourselves whether we really perceive a world, on the contrary, we must say: the world is what we perceive”, wrote Husserl in “Phenomenology of Perception” in 1945, explaining that our relationship with the world passes through the senses before being consciously perceived and explained by a certain intellectual construct.

This direct perception, which begins with the senses, was at the heart of musical and pictorial creation in the 19th century.

This questioning of the awareness of the world through the arts is called “Impressionism” and emerged around 1870.

Impressionism seeks to break the codes previously established by Romanticism, which focused on capturing clear, strong, dramatic, and internal emotions, to make way for the impression of an external emotion, much more centered on atmosphere.

The objective of this artistic movement was to give way to diffuse, rather than imposed emotion, focusing on a moment over a specific and realistic detail.

It is not a static art form, but one that attempts to express sensations.

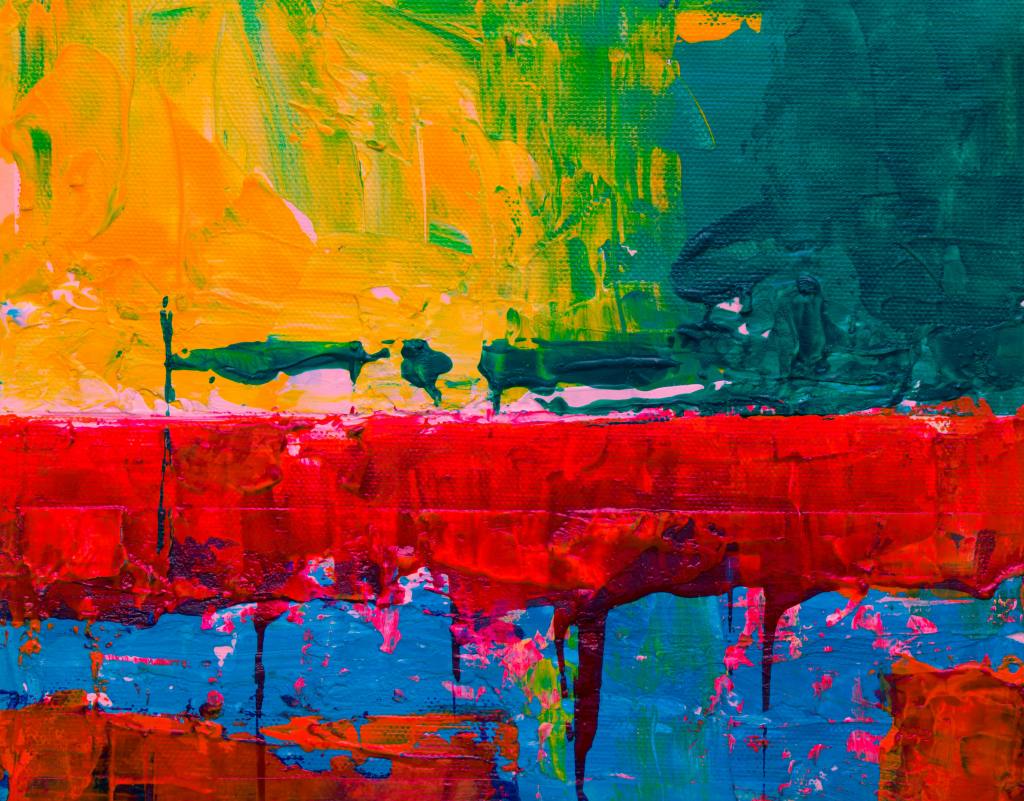

In painting, Impressionism focuses on capturing light, color, and present moment.

It typically features light colors applied in small strokes, and outdoor landscapes blended with a sense of vibration and movement.

When we look at Claude Monet’s painting The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil, we are first struck by the atmosphere, which is like a dream. The closer we get to the details, the more they disappear, reflecting a desire to set aside the classical and realistic codes of painting. The artist does not seek to satisfy the cold and demanding gaze that expects a perfect resemblance between reality and its representation.

These artists, who disrupted the usual codes of creation in their respective epochs, also pursued this movement in the world of music.

Artists such as Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and Satie took part in Impressionism by composing not strictly defined and immediately identifiable emotions, but rather an almost dreamlike and floating atmosphere.

Through the use of ambiguous harmonies, pentatonic scales that do not use dissonant chords, flexible rhythms, and rich, colorful orchestration, the sound of musical impressionism tends toward a realization resembling dreams and at times, water.

The light colors in the paintings can be compared to stamps, the light to harmonies, and the vibrations to supple rhythms.

As we said at the beginning, the question is not whether we really perceive a world, but whether the world exists as we perceive it.

This question became particularly relevant at the end of the 19th century, and the first person to raise it was Edmund Husserl, an Australian philosopher and mathematician.

In “Phenomenology of Perception”, Husserl seeks to establish the link between human consciousness and its relationship to the world.

Like impressionism, phenomenology attempts to represent the appearance of the world as we experience it in the moment, before our brain reconstructs a fixed image of it.

To demonstrate that there is an essential relationship between consciousness and its environment, Husserlian phenomenology approaches the phenomenon as itself, based on “épochè”, which means “cessation” in Greek. It is a technique that allows us to set aside our natural prejudices, logic, and categories in order to analyze the very essence of our experiences.

In contrast to traditional metaphysics, which conceives of the world in terms of ideas, we seek to return to “things themselves” through intuition and based on singular examples, on a subjective experience of the world.

In fine, phenomenology, by placing experience, direct feeling, and detached conscious awareness at the center, allows for a spontaneous study of things and phenomena as they ordinarily present themselves.

The 19th century challenged artistic norms and society’s desire to classify and “mathematically” interpret the outside world, focusing instead on an instinctive and subjective approach to our surroundings and inner selves.

Thanks to these artists and thinkers, the cultural world presented a new vision of life, of humanity, and of our desire to understand and categorize everything, making way for a life of sensory experiences and a less rigid pace than that imposed in the previous century.

Art will always be free, and it is important to take advantage of this to recreate norms that we sometimes think are set in stone.

Luna Serrano

Sources:

Leave a comment